How ‘Progressive’ Education Patronises the Poor

My article for Spiked Online.

The only responsibility schools have to working-class kids is to give them a good education.

Source: How ‘progressive’ education patronises the poor

Teachwell Progressive Education, Social Class Accountability, Child-Centred, Children, Discipline, Philosophy, Prejudice, Primary School, Secondary School, Teachers, Teaching Assistants 0

My article for Spiked Online.

The only responsibility schools have to working-class kids is to give them a good education.

Source: How ‘progressive’ education patronises the poor

Teachwell Teaching and Learning Children, Primary School, Secondary School 12

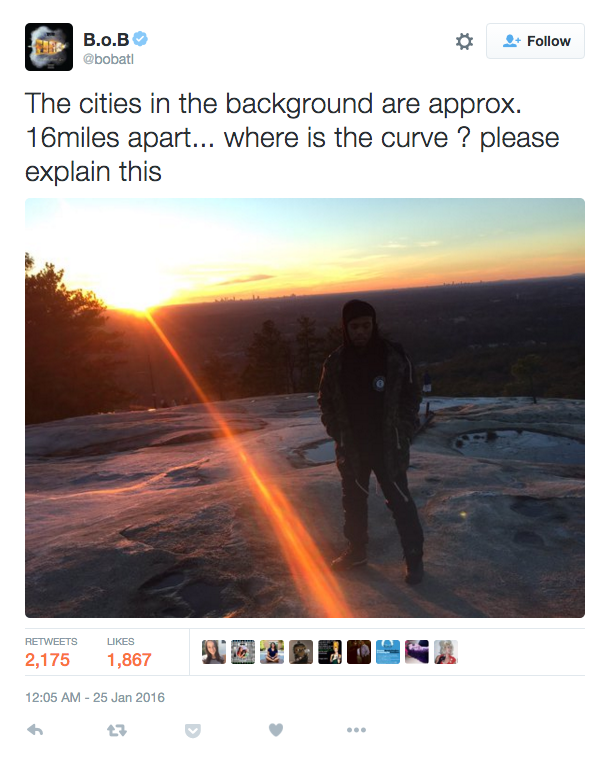

According to the rapper BoB, the Earth is flat. His recent tweeting activity included this insight as well as pictures to prove he was right.

Also, how does one explain this?

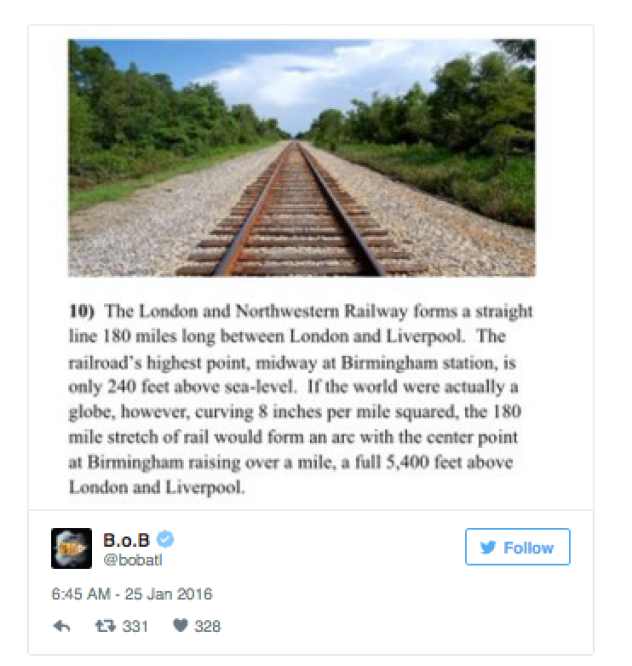

Or this?

BoB is not alone, though – there is, of course, the Flat Earth Movement who agree with him.

Hell, they go one . Further, they have VIDEOS ON YOUTUBE.

200 ‘proofs’ of a flat earth here people.

If that won’t convince you then maybe this better-edited one will:

This video even has the great insight that while the scientists ‘claim’ that the water is subject to gravity, that’s not what we see.

Has anyone seen gravity? Anyone? Anyone at all?

And the conspiracy theories involving Freemasons and NASA aren’t far behind. What is missing, however, is how the Ancient Greeks came to the idea of a spherical earth. No doubt there is a time travel conspiracy there too.

Those people who genuinely believe that group work on the internet is a good way of learning, supporting the supremo charlatan Mitra, might want to think about how children will be able to filter out good and bad ideas. Or are they to ‘make up their mind’?

I suspect, unfortunately, that the answer to the last question will be yes. A belief in equality seems to have morphed into a conviction that all ideas have worth and are equally valid. One can’t say that an idea is wrong because it might hurt someone’s feelings.

Tough. While everything should be open to discussion, let us not pretend that the evidence for some ideas and theories is not overwhelming. The bar to disprove the Earth is spherical is incredibly high due to the accumulated evidence. As teachers, we owe it to our pupils to explain this explicitly and with examples, as well as debunking some of what is on the internet.

The need for knowledge is there regardless of the web. But given the Internet, the need is in many ways greater. Future generations need to know to cut through the misinformation there. What questions to ask about sources, why some are more valid than others. And I do believe that we should start as we mean to go on, at primary level. I don’t believe that any primary child should be researching on the internet until at least Year 5 and even then they should have a bank of websites they know are reliable (e.g. BBC) which they know to turn to.

It highlights the importance of the fact that if we are going to allow children to use the technology, we also need to teach how it can and is abused to propagate bad ideas and how these can be countered and avoided.

Human beings are capable of shedding bad ideas and theories. We need to teach when, how and why we do this so that they can build on past achievements rather than going round in circles regarding ideas that have been thoroughly debunked.

Teachwell Education Debate, Teaching and Learning Cross-Curricular, KS1, KS2, Primary School, Subjects, Teachers 2

There are times when I get it completely wrong.

At first glance, the paperclip butterfly picture, introducing Sinead Gaffney’s (@shinpad1) article in TES this week, jumped out as a trigger warning of child-centredness. Her article though is an eloquently argued piece, insightful and gives coverage to the realities of teaching younger children which are more often than not ignored.There is much I agree with, including, the fact that a secondary set up with specialist teachers in all subjects would hinder not help children, especially in KS1.

The one issue that I did find myself hesitant to agree with was the value of cross-curricular teaching, especially the value of ‘no subjects,’ ‘throw it all in’ path that Finland is going down.

Cross-Curricular Done Badly (Very Badly):

The bad name that cross-curricular teaching has comes mainly from the result of schools adopting badly constructed schemes of work. Frivolous topics, tenuous links between subjects and, even more, tenuous links to the National Curriculum. These schemes of work were supposed to meet the dual objectives of allowing teachers to plan less from scratch, a noble goal, and cover the curriculum.

Given the adaptations necessary to make these plans appropriate for my class, I did not find them less time consuming. As for coverage, the small print of any scheme of work is evident, it is the school’s role to ensure curriculum coverage, yet many schools assumed this was ensured by the scheme.

When I started my NPQML, my school were using a mixture of a well-known scheme of work combined with a skills-based approach by the latest 21st-century skills charlatan.

I went through the schemes of work lesson by lesson, task by task, for each year group. It was not a pretty sight.

One lesson, in particular, sticks out in my mind. It was a lesson on Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, which contained eight objectives from history, music, and art.It involved the children learning a little about her, listening to Greensleeves and then drawing a picture of her. I still can’t work out what the point of that lesson was.

Now I appreciate that many teachers used these lessons as the basis for their planning, but I also know many who were dependent on the schemes and taught them straight.Also, these formed what some teachers would assume were ‘good practice’ when creating their units. Again, it was just spreading bad practice and ideas. The divorcing of teachers from the National Curriculum was an issue that came to the fore when the new curriculum was being implemented in my last job.

Subject Specialisms:

Much of the problem is a lack of subject specialism, BUT I don’t think that this needs to be a problem in primary if we were to focus on what is important.

First, the selection of subject leaders is a fraught affair and more than once I have seen those with degrees in subjects or specialisms not being given posts. When Quirky Teacher brought this up in a post a few weeks back, there was an outcry of ‘being good at a subject does not make you a good teacher.’

Agreed, but we are not talking about recruitment here. We are talking about trained primary teachers, who are qualified to teach and have a subject specialism. When I think of all I was able to do when I took on the history role, training I provided, resources, support, guidance, one-to-one planning, etc. it makes the decision of one school to refuse me the post (it was comeback from them – long story) seems nothing short of a criminal waste. How many primary schools have a teacher with a Masters in Political Science?

Second, subject leaders are not always given appropriate training, time to develop their subject knowledge or time to support other teachers.

Third, the emphasis on marking, assessment, tracking, etc. has reduced the time available for subject leaders to train teachers in meetings. Faddy initiatives introduced via staff meetings also wastes time.

Last, being a subject leader had become synonymous with being ‘the person who puts the order in for resources’ rather than leading the subject.

Cross-Curricular Done Well?

It might surprise some, but I don’t agree with a rigid timetable at primary where there is an hour every week (or 5 for Literacy and Numeracy each) for a subject. I found this approach did not work for the children and age ranges I taught (especially younger ones).

I think we don’t use our flexibility in primary enough at times and many newer teachers need support to gain the confidence to do this.

So what do I think is cross-curricular done well? Well for a start it involves making only meaningful links across the curriculum. Below is an example:

The units were based on flexible schemes of work which simply showed a breakdown of the units (all of which were question-based – I know how progressive of me!!).

However, we selected the best, most academic, schemes of work possible for each subject, and not one that claimed to ‘do it all.’

Curriculum coverage for each subject and unit was checked, and the unit breakdowns were adjusted to ensure that there was coverage.

There was total clarity for existing, and new teachers could see what was being covered and in which unit. This was, I stress a one-off, resulting from the introduction of the new curriculum.These would need reviewing and adjusting each year.

So what did this mean for us regarding our planning? Well, each half term (although some of the units cross half terms) a medium-term map which contained the unit breakdowns was produced (this was a simple copy and paste job).

Therefore, week to week the subjects we taught (with the exception of Literacy and Numeracy) were different. Where a subject had been discreet in the medium term plan, we made a decision to either teach it each week or to block it. Again adjustments would be made based on the experience of teaching these sequences.

The flexibility in the primary curriculum enabled us to do this, and I think we would have been poorer if we had to stick rigidly to one history lesson a week say.

When teaching the Stone Age to Iron Age Unit, we taught history lessons on the stone age, before focusing on the art unit creating cave paintings, and then moved back to History and taught the Bronze and Iron age. It simply would not have made sense to flit around with an art lesson each week that referred to history lessons taught 3 or 4 weeks back.

So do I believe that cross-curricular teaching can work? Yes but not by rejecting subjects or an academically rigorous approach but by embracing it and using the timetable flexibility primary teachers have to sequence lessons logically.